Intellectual property: enabling next-generation innovation

The UK’s intellectual property (IP) framework is essential to unlocking investment for scientific research, ensuring continued development of the medicines people need.

The UK has one of the most advanced and well-established frameworks for pharmaceutical IP rights anywhere in the world. This reflects the culture of scientific innovation and international collaboration that has long been encouraged in the UK and it is a cornerstone of the country’s success as a global centre for life sciences innovation.

Following significant investments into the high-risk, lengthy process of discovering, developing, and manufacturing new medical breakthroughs, a strong IP framework ensures that if a medicine makes it to the market, it will be protected from unfair competition for a limited period time.

Through the incentives and rewards that a strong IP framework provides, research institutions and companies of all sizes can turn ideas into treatments that address unmet medical needs, improve people's lives, and create value and jobs across the country. As a result, our IP framework forms a key part of the UK’s ability to attract inward investment to support cutting-edge research into the next generation of medicines and vaccines to benefit society.

Unpacking the UK's pharmaceutical IP incentives

What is a patent

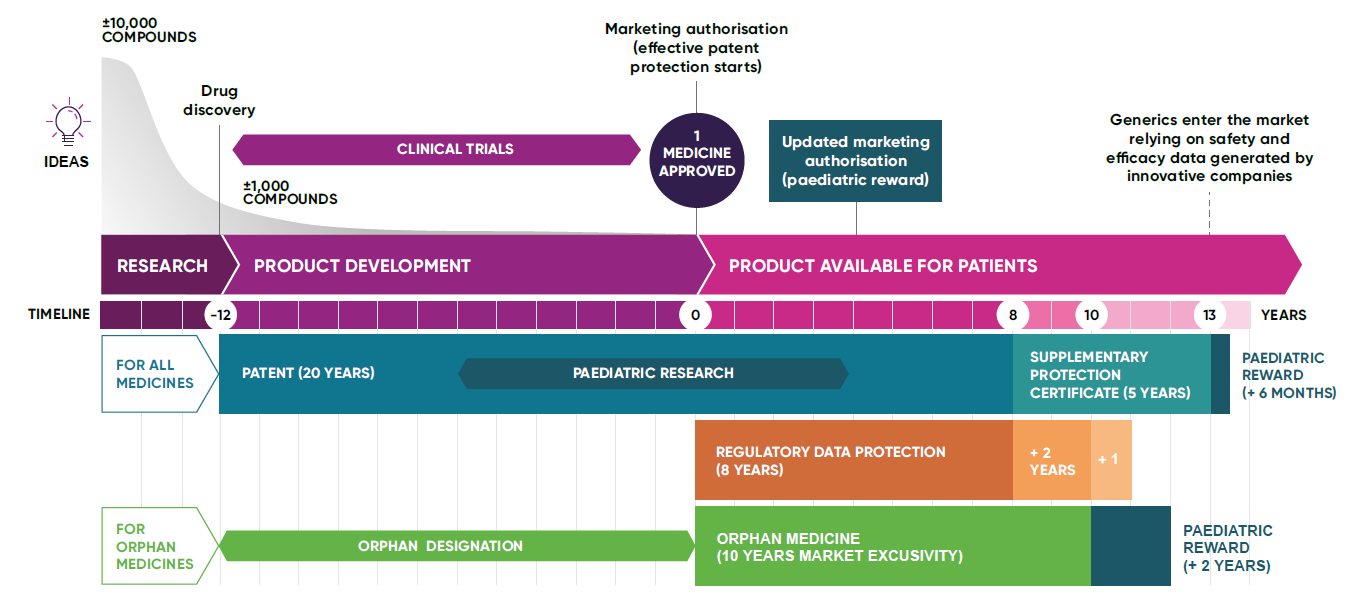

A patent is a legal protection granted to the inventor of a new medicine, which gives them the exclusive right to manufacture, use, and sell the medicine. Patents prevent others from copying and selling a medicine without permission during the set period, known as the ‘patent term’. Initially granted for five years, patents are extendable up to a maximum of 20 years. On average, it takes 12 years from a patent being granted to a medicine being used in a health system for the first time. This is due to the lengthy clinical development process and stringent regulatory approval process that new medicines are subject to.

In the UK, patents can only be granted for an invention that is new, inventive (that is, not obvious), and capable of being made or used industrially. Patents encourage innovation by allowing innovative biopharmaceutical companies to recoup the large investments in research and development (R&D) needed to create new effective treatments.

Pre-Patent: This is the initial phase of R&D where scientists work to understand a disease and identify potential treatments. Companies can be looking at tens of thousands (10,000+) of potential treatment candidates, almost all of which will fail. No patent protection exists at this stage.

Pre-approval: During this stage of product development, the focus is on conducting clinical trials to test the safety and effectiveness of a potential new treatment. This is crucial for gaining regulatory approval. Running large-scale clinical trials is enormously costly; with companies making huge investments with no guarantee that a medicine will ever make it to market. Most do not. Those that do can be life changing.

Post-approval: After a medicine is approved by regulatory authorities, it enters the market for clinical use. This is called marketing authorisation. In many countries, including the UK, it must also then be assessed for cost effectiveness before it can be used by public health systems like the NHS. This is called a heath technology assessment. Only when this stage is also complete does a company start to see a return on its investment – often well over a decade from when the patent was first secured leaving only a narrow exclusivity window for innovators. The company continues to pay for monitoring of medicines safety and efficacy after approval.

Regulatory data protection

This protection prevents competitors from using the innovator’s clinical trial data to gain approval for generic medicines for a certain period. Regulatory data protection safeguards the investment that innovative companies make to generate data that shows the quality, efficacy, and safety of a medicine. It ensures that the innovator can exclusively market their medicine, helping to recoup the investment made in its development.

Regulatory data protection is made up of eight years of regulatory data protection, and ten years of market protection, that run in parallel from initial marketing authorisation. An additional one-year is an optional extension to the market protection period, available in cases where a new therapeutic use of the medicine has been approved which brings significant clinical benefit compared to existing medicines.

Paediatric medicines

During the medicines development process, special incentives known as a ‘paediatric reward’ are often provided to encourage the development of medicines specifically for children, due to the unique medical needs of children. These incentives seek to make sure that where appropriate, medicines are adequately studied in children and developed to meet their needs, including the need for age-appropriate formulations.

Orphan medicines

These are medicines developed specifically for rare diseases. Companies are often offered incentives like market exclusivity to encourage research into conditions that might otherwise be overlooked due to a small patient population.

Supplementary protection certificates

A large part of the patent term can be used up during clinical development and getting the authorisation required to market a medicine. This means that by the time a medicine can be sold, and innovators rewarded for the value of their discovery, a considerable amount of the patent term will have gone by.

In the UK, supplementary protection certificates (SPCs) are available to make up for the time taken to secure marketing authorisation for medicines and other biopharmaceutical products. These certificates offer up to a maximum five years of protection following the expiry of a patent. However, the combined patent and SPC protection period from marketing authorisation cannot be more than 15 years in the UK.

Generic and biosimilar medicines

Once the patent and any other market exclusivity protections on a medicine expire, other companies can produce generic or biosimilar versions. These are typically less costly because there are no clinical development costs involved, but manufacturers must continue to prove their generic medicines are equivalent and biosimilar medicines near-identical to the original branded medicine in terms of safety and effectiveness.

By protecting and supporting innovators in this way, the NHS now has tens of thousands of low-cost generic medicines which have continued to help patients many decades after the patents on their branded variants expired. Without patents, many of these medicines would never have been invented, or received the investment needed to bring them to patients.

Last modified: 08 January 2025

Last reviewed: 08 January 2025